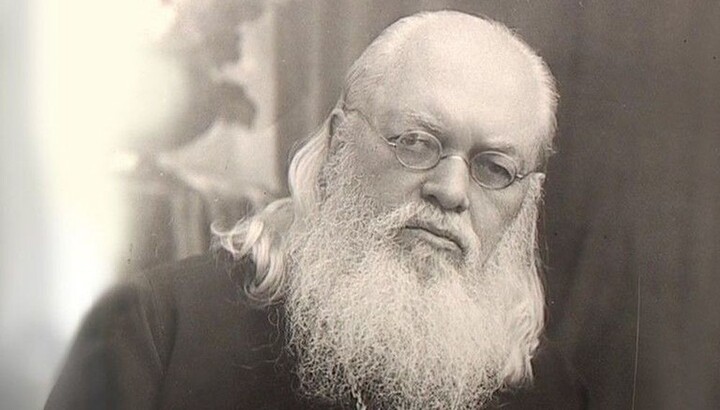

Saints of the 20th Century: Special St Luke of Crimea

The personality of St Luke is big and many-sided. However, there are traits that most vividly manifest in all his activities. Let's try to find out which ones.

Childhood and youth

Valentin Felixovich Voyno-Yasenetsky (his civil name) was born on 15 April 1877 in Kerch, to pharmacist Felix Stanislavovich and his wife Maria Dmitrievna, and was the fourth of five children. The Voyno-Yasenetsky family (for some time, the hierarch wrote his surname in reverse – Yasenetsky-Voino) comes from Belarusian lands. This family was quite old and noble but had become impoverished by the second half of the 19th century.

His father, Felix Stanislavovich, trained as a pharmacist and managed to open a pharmacy in Kerch. However, the business did not succeed, and after two years, the pharmacy had to close, and he had to take a job with a transport company.

The Voyno-Yasenetsky family was not particularly religious. "I did not receive religious upbringing; as for inherited religiosity, I probably inherited it from my father," the hierarch later said. His father was Catholic, and his mother was Orthodox.

In 1889, the Voyno-Yasenetskys moved to Kiev, where Valentin graduated from a gymnasium and an art school in 1896. In choosing his future path, one of the key traits of the future confessor's personality emerged – the desire to serve others. Of the two options, medicine or painting, he chose the former, as it would allow him to help people more. However, his first attempt to enter the Medical Faculty at the St. Vladimir University in Kiev (now the Taras Shevchenko University) ended in disappointment, as he did not pass the entrance exam. But since his grades were still quite high, he was offered a place at a different faculty.

Valentin chose law. However, jurisprudence did not interest him, and after a year, he dropped out. He then went to Munich (Germany), where he took painting lessons from the well-known artist Heinrich Knirr.

After returning to Kiev, he started sketching the streets, often depicting the homeless and beggars he encountered. This experience finally inspired him to apply to the Medical Faculty and help these people.

"I studied medicine with the sole purpose of being a zemsky (district), peasant doctor for my entire life," he said after graduating from the Medical Faculty of the St. Vladimir University, where he studied from 1898 and graduated as one of the top students in 1904.

Work as district doctor

Before becoming a district doctor, he went to the Russian-Japanese War as part of the Kiev Medical Hospital of the Red Cross. This hospital was based in Chita. There, he married the nurse Anna Lanskaya.

The story of their marriage is ambiguous. The fact is that Anna Lanskaya was very pious and took a vow of celibacy. Apparently, it was not a monastic vow but rather a secret vow. In Chita, she rejected two doctors who proposed to her, but she accepted Valentin Yasenetsky’s proposal. The night before their wedding, something happened to her, which St Luke later described in his autobiography: "...the night before our wedding in the church built by the Decembrists, she prayed before the icon of the Saviour, and suddenly it seemed to her that Christ turned His face away, and His image disappeared from the icon."

Nevertheless, they got married. She was tormented by guilt for breaking her vow, as the saint wrote: "The Lord severely punished her with unbearable, pathological jealousy."

After returning from Chita, Valentin Felixovich worked in district hospitals in small towns: Ardatov, Verkhny Liubazh and Fatezh. This work was difficult and unrewarding, demanding all of his energy. There were a lot of patients, requiring attention, and the working conditions and necessary medical supplies were extremely inadequate. During this time, the family had two children.

In the autumn of 1908, Valentin Felixovich went to Moscow and enrolled in an external programme at one of the Moscow surgical clinics. His academic work progressed well, but it did not provide a livelihood. Therefore, in early 1909, he took up the position of chief doctor at the hospital in the village of Romanovka in the Saratov province; and in 1910, he became the chief doctor at the hospital in the town of Pereslavl-Zalessky in the Vladimir province. That same year, the family had their third child.

In Pereslavl-Zalessky, the future saint worked until 1916. During these years, he combined his work as a doctor with scientific research, dedicating all of his weekends and holidays to it. In 1916, he defended his doctoral thesis on the topic "Regional anesthesiology". The family had a fourth child.

During his 13 years of work as a doctor in various cities, Valentin Felixovich, by his admission, rarely went to church. However, in the last few years, he began to find the opportunity to attend the cathedral.

In 1917, his wife developed symptoms of tuberculosis, and the family moved to Tashkent due to the more favourable climate, as well as some fortunate circumstances. In Tashkent, where Valentin Voyno-Yasenetsky worked as the chief doctor of the Tashkent hospital, he was caught up in the revolutionary events.

Priesthood and hierarchy

In 1919, the Bolsheviks brutally suppressed the anti-revolutionary uprising of the Turkestan regiment, with many soldiers and civilians being executed by firing squad Voyno-Yasenetsky was also taken to the railway workshops, where speedy trials were held and executions took place. He was saved only because one of the commanders recognised him and sent him back to the hospital. However, for his wife, the ordeal proved to be fatal. She began to die away rapidly and passed at the end of October 1919, at the age of 38.

“The last days of her life had come. She was burning with fever, completely lost sleep, and suffered greatly. For the last twelve nights, I sat by her deathbed; and during the day, I worked at the hospital,” wrote St Luke in his autobiography. Even after her death, he read the Psalter over her coffin for another two nights. The words of one of the Psalms struck him with such clarity as a personal message about what he should do next: "He settles the barren woman in her home, as a joyful mother of children" (Ps. 112:9).

After reading this, Valentin Felixovich understood that God was pointing him to one of his operating room nurses, Sofia Sergeevna, who had recently lost her husband and was childless. He proposed that she become the mother of his children, without marrying him, and Sofia Sergeevna agreed.

After his wife’s death, the future hierarch began to visit the church more frequently and participate more actively in the life of the eparchy. He spoke at meetings and offered interpretations of the Holy Scriptures. In early 1921, Bishop Innocent of Turkestan (Pustynsky) suggested that he take holy orders, to which Valentin Felixovich immediately agreed. This marked the beginning of his path as a clergyman in the persecuted Church.

Immediately, one of the traits of his character became evident, which can be described as determination. Many holy fathers regard this quality as one of the main conditions for the salvation of a person. It is not enough to simply believe and follow Christ; one must do so with determination and the readiness to endure everything but never betray Christ. This determination manifested in Father Valentin’s life when he began wearing a cassock, placed icons in the operating room, and prayed before surgeries and important tasks. In those times, this was a challenge to the godless authorities, a confession of faith in the face of possible persecution.

In the same year, 1921, Father Valentin spoke at a trial where Tashkent doctors were accused of failing to assist Red Army soldiers. During this trial, he had his famous dialogue with Yakov Peters, the head of the Tashkent Cheka (the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission):

“– Tell me, priest and Professor Yasenetsky-Voyno, how is it that you pray at night but cut people during the day?

– I cut people for their salvation. And in the name of what do you cut people, сitizen public prosecutor?

– How is it that you believe in God, priest and Professor Yasenetsky-Voyno? Have you seen your God?

– I have indeed not seen God, citizen public prosecutor. But I have operated on the brain many times, and when opening the skull, I have never seen intellect there. Nor have I found conscience there either.”

Yakov Peters was one of the most brutal leaders of the Cheka, and only a very courageous man could answer him in this way and oppose his accusations.

In 1923, the Renovationist schism reached the Tashkent Eparchy. Bishop Innocent strongly opposed this, but many prominent clergy fell into schism, and he had to leave the eparchy. In this situation, Father Valentin was consecrated as a bishop by two exiled archbishops, with a prior monastic tonsure under the name Luke. His consecration took place on 31 May 1923, and just 10 days later, on 10 June, he was arrested. After a lengthy investigation, he was exiled to Yeniseisk.

"This marked the beginning of eleven years of my imprisonment and exile," he would later write.

Arrests and exiles

During his first exile, St Luke had to change several places of residence in the harsh Arctic region. Despite the difficult living conditions, he carried out extensive medical practice, conducted religious services and preached. He was released in 1925, and at the beginning of 1926, he returned to Tashkent. However, he couldn’t secure a position as a doctor in any of the hospitals and was forced to pursue private practice.

As for the bishop's church activities during this period, they were somewhat ambiguous. Firstly, it is unclear why he refused to consecrate the church of St Sergius of Radonezh, where the exiled Renovationist bishop had served before him. Secondly, he submitted a request for retirement following a series of decrees from Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky), the deputy of the Patriarchal Locum Tenens, regarding his transfer to other eparchies. "This was the beginning of a sinful path and God's punishments for it," he wrote later in his autobiography.

In 1930, St Luke was arrested again and exiled to the Northern regions. At the same time, he was finishing his monumental work “Essays on Purulent Surgery”. Due to his successful scientific activity, the Bolsheviks made him an attractive offer: to head the surgical department in exchange for renouncing his ecclesiastical office. "Under the current circumstances, I do not consider it possible to continue my ministry, however, I will never relinquish my ordination," responded St Luke.

In 1933, he was released. In 1934, his monograph “Essays on Purulent Surgery” was published, bringing the author worldwide recognition. On returning to Tashkent, St Luke resumed his medical practice and earned a doctorate in medical sciences in 1936. The same year, he successfully performed surgery on N. Gorbunov, the secretary of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In gratitude for saving his life, Gorbunov offered Voyno-Yasenetsky the position of head of a research institute in Dushanbe (then Stalinabad). Vladyka made it a condition of his consent to open a church in Stalinabad, which was refused. There also followed several other tempting offers on condition of resigning from the priestly ministry, which St Luke rejected.

In 1937, he was arrested for a third time. He was accused of forming a "counter-revolutionary church-monastic organisation," espionage for foreign intelligence agencies, and the murder of patients on the operating table, among other charges. These were the years when those arrested were pressured to implicate their "accomplices" to extend the purges to larger sections of the population. The bishop was subjected to the "conveyor" torture: for 13 days he was continuously interrogated by successive investigators but he did not implicate anyone he knew.

He was sentenced to a 5-year exile in the Krasnoyarsk region. This relatively light sentence was likely due to St Luke's international reputation as an outstanding surgeon.

Krasnoyarsk and Tambov Eparchies

At the outbreak of World War II in 1941, he was appointed as a consultant to all hospitals in the Krasnoyarsk region and as the chief surgeon of the evacuation hospital. There were many wounded, and the bishop worked tirelessly, often leading to neurasthenia. In 1942, he was consecrated as an archbishop and appointed to oversee the Krasnoyarsk Eparchy. In 1943, he participated in the Local Council in Moscow, where Patriarch Sergius (Stragorodsky) was elected. He was also elected as a member of the Holy Synod, but due to the long distances, he had to refuse this position.

In 1944, Abp Luke was appointed to head the Tambov Eparchy, and the military hospital also relocated there. Interestingly, a few months later, Patriarch Sergius wanted to transfer him to the more prestigious Tula Eparchy but this was opposed by G. Karpov, the commissioner for the affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church, who presented several claims against Archbishop Luke to the Patriarch:

- He hung an icon in the surgical department of evacuation hospital No. 1414 in Tambov;

- He conducted religious services in the hospital’s office before surgeries;

- On 19 March, he attended a regional meeting of doctors from evacuation hospitals dressed in his episcopal vestments.

- He sat at the head of the table and, still in his vestments, gave a report on surgery, among other things.

The commissioner demanded that all this stop. Again, we see Abp Luke's uncompromising nature. If he was a believer, he would pray regardless of the circumstances. If he was a bishop, he would attend all events, even secular ones, in the bishop’s vestments.

Ultimately, he was allowed to stay in the Tambov Eparchy. There, he developed an active ministry. At the time of his arrival, there were only three functioning churches in the eparchy, but within two years, there were already 24. He established an archdiocesan choir, ordained many active parishioners as priests, drew up a penitential rite for the Renovationist priests, and developed a plan to revive religious life in Tambov. The plan included religious education for the intelligentsia, the opening of Sunday schools for adults, and more.

St Luke may have been overly optimistic about the relaxation of church persecutions that occurred in 1943. However, the Holy Synod had a different view and rejected the plan.

In May 1944, Patriarch Sergius passed away, and during the preparations for the Local Council to elect a new patriarch, St Luke opposed the election of the patriarch on a non-alternative basis. He believed that the election process should follow the procedure outlined by the Local Council of 1917-1918, which involved nominating several candidates, voting for each of them, and determining the winner by lot.

However, this was very far from the plans of the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church. As a result, St Luke was the only bishop who was not invited to the Local Council, which elected Alexis (Simansky) as the next patriarch.

The Crimean Eparchy

In 1946, Vladyka Luke was awarded the Stalin Prize of the First Degree for his works “Essays on Purulent Surgery” and “Late Resections of Infected Gunshot Wounds in Joints”. The same year, he was transferred to the Crimean Eparchy. On arriving in Simferopol, he behaved very independently. He did not personally visit the commissioner for the affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church in Crimea, Y. Zhdanov, and did not coordinate with him the appointments or movements of priests in his diocese.

The Crimean Eparchy had been devastated by persecution and the war. Many churches were destroyed, and those that remained, the Soviet authorities tried to close by all means. Abp Luke tried to protect the churches and repair them where possible. He devoted a lot of effort to improving the moral conduct of the clergy, demanding strict adherence to the canons and rules.

In 1949, there was an attempt to accuse Abp Luke of propagating hatred towards the Soviet government and to seek his arrest or, at the very least, a transfer to another eparchy. This attempt failed, as there was no substantial evidence for such accusations in his activities. On the contrary, his publications in the “Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate” demonstrated his loyalty to the Soviet government. "We have no reason to be hostile to the Government, as it has granted full freedom to the Church and does not interfere in its internal matters," a quote from issue No. 1 of 1948. The only thing his adversaries managed to achieve was a reduction in the number of his sermons.

The end of life and canonisation

In Tambov, Archbishop Luke’s eyesight began to deteriorate; and in 1955, he was completely blind. He accepted this new trial as God’s will: "I bear my blindness complacently and with complete devotion to the will of God," he wrote in one of his letters. "For my bishop’s activity, blindness does not present a complete obstacle, and I believe I will serve until my death." And so it was – fully blind, Archbishop Luke continued to perform Divine services from memory.

On 11 June 1961, St Luke reposed in the Lord. On 22 November 1995, the Holy Synod of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church canonised him as a saint. To this day, there are numerous accounts of miracles and help attributed to the saint, and his veneration continues to grow in many countries each year.

Epilogue

What traits most fully characterise St Luke's personality? Two of them have already been mentioned: determination and a desire to serve people. Having decided to dedicate himself to serving God, he never looked back, despite the opportunities to do so. And he always served people, seeing this as his calling.

Another trait was honesty. He was never afraid to tell people straightforwardly what he thought, even though this was extremely risky and often led to serious trouble for him. The flip side of this was that he trusted people. Unable to lie, he assumed that those around him were also honest with him. This trait was often exploited. Archbishop Innocent (Leoferov) of Kalinin, former secretary of the Tambov Eparchy, recalled that when he was seeing off Abp Luke from Tambov to Crimea, they had the following exchange:

"We were alone in the compartment, and the Archbishop asked:

– Tell me, what is the greatest vice I should avoid?

– Please, don’t trust slanderers, I said. Based on the complaints of liars, Your Grace, you sometimes punished innocent people.

– Really? he said in astonishment. Then, after thinking for a moment, he added: I just can’t part with this. I can’t stop trusting people."

Another trait of the saint was the ability to admit his mistakes and declare them publicly, to ask forgiveness from people regardless of their social standing. Archbishop Luke spent several days asking forgiveness from a parishioner who had been accidentally hit by a book.

However, the most significant trait of St Luke was his absolute trust in God and his confidence in Divine Providence. He could calmly follow the Red Army soldiers who arrested him, knowing it would likely lead to his death, but when the Lord spared him from danger, he would return to his clinic and operate on the sick as if nothing had happened. He could stand up to the cruel Chekist Yakov Peters, who could execute him without trial, fully confident that "… not a hair on your head will perish…" (Luke 21:18) without God’s will.

Saint Luke, pray to God for us.