God in a “krysania”: Why, for Antonych, Bethlehem moved to the Carpathians

Lemko Magi, a golden nut–Moon in Mary’s palms, and the Lord riding in a sleigh. How Bohdan-Ihor Antonych turned Christmas from a biblical story into a personal experience for every Ukrainian.

Close your eyes. For a moment, forget everything you have seen in classical icons. Forget the palms, the hot sand of the Judean desert, the flat roofs of white houses.

Breathe in. This place does not smell of incense and myrrh. It smells of wet sheep’s wool, pine resin, stove smoke, and that particular, ringing cold that snatches your breath away.

We are in the world of Bohdan-Ihor Antonych – a world where the biblical map has been decisively crossed out and drawn anew, not with ink, but with frost on glass.

This poet pulled off a daring, almost impudent, yet brilliant theological trick. He took the Nativity and moved it from a historical “there” into a geographic “here.” In his poems, God is not born in some foreign Palestine. He is born at home – in the snowbound Carpathians, where the crunch of snow underfoot sounds like prayer.

A sleigh instead of a cloud

“God was born upon a sleigh

in Duklia of Lemko land.

Lemkos came in krysania hats

with the round Moon in their hands.”

These four lines are an absolute masterpiece of Ukrainian-style “magical realism.”

Picture it. Night. Mountains wrapped in heavy white coats. And along the road rides not a Roman chariot, not a royal procession, but an ordinary village sleigh. The runners creak as they cut through the crusted snow. The horses (or oxen) snort, releasing clouds of steam.

Antonych “domesticates” the Creator. It is as though he is saying: God so loved this world that He took on not only human flesh, but human everyday life.

He accepted the rules of our climate. If it is winter here, if the drifts are waist-high – then God will sit in a sleigh.

Why Duklia? It is a real little town in Lemkivshchyna. But for Antonych it becomes the center of the Universe. The poet does not care what is written on maps. What matters is that God is everywhere. Which means Bethlehem is wherever people believe in Him. That night, Bethlehem was in Duklia. Today it might be in Bakhmut, in Lviv, or in a dark Kyiv high-rise with no electricity.

Magi in hats

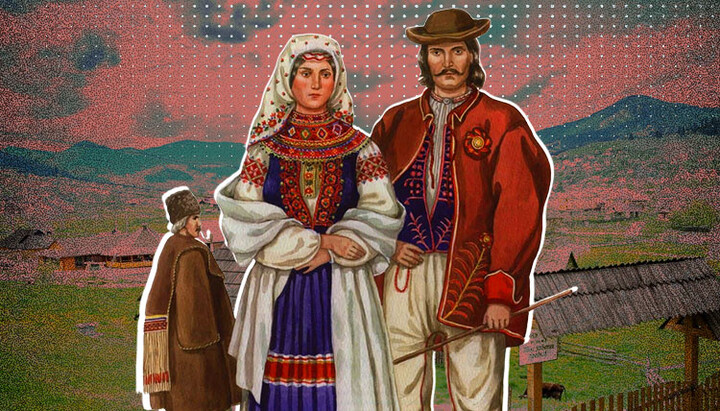

Who welcomes this strange, “snowy” God? There are no exotic kings in silk and turbans here. To the manger (which likely smells of a Carpathian stable) come Lemkos.

They wear krysanias – broad-brimmed felt hats. They wear heavy hunias made of sheepskin. Their hands are rough and windburned – the hands of people who have worked the earth all their lives.

This is a stunning democratization of the Gospel.

Antonych removes the distance. The Magi are not “them,” ancient sages out of books. The Magi are “us.” Our grandfathers, our neighbors. Those who know how to walk the mountains and who understand the price of warmth.

And their gift matches them. They do not carry gold, which is useless in the mountains. They bring “a round moon.”

Pause and take in the image. The Moon – that vast, cold companion of the Earth, a cosmic body. And the Lemkos take it down from the sky like a Christmas ornament and lay it at the Infant’s feet.

Then comes a miracle of scale.

“Snowstorm whirls the night around

chimney, roof, and quiet hut.

In the hands of gentle Mary

rests the Moon – a golden nut.”

The cosmos shrinks to the size of a Carpathian cottage. The Universe becomes intimate and comprehensible. The fearful, icy Moon, warmed in the Mother of God’s hands, turns into a “golden nut” – a toy for her Son.

Mary, in Antonych, is not simply an icon. She is a Mother warming her hands for her Child. She is “ours.” She knows how to wrap the Infant when a “zaviia” – a snowstorm – howls outside.

The prayer of a snowdrift

Antonych was often called “a pagan in love with Christ.” It is a beautiful label, but not quite accurate. Antonych is not a pagan. He is a singer of the holiness of matter.

In his Nativity, it is not only people who pray. Snow prays. Wind prays. Deer in the forest pray, and the straw on the roof prays.

For him, Christ’s coming is an event on a cosmic scale – one that sanctifies every atom. Nature is not merely a backdrop for human salvation. It is a participant.

In his poems we feel this saturated vitality, this energy of life. Christmas is not a quiet candlelit holiday. It is an element, a force – the kind of joy that swells your ribs until you want to shout together with the wind.

“Christ is born!” – and in reply it is not only church bells that resound, but the mountains themselves. God is dissolved in this frosty air. Every snowflake is a tiny letter from Him.

God, our fellow countryman

Why do we need this mystical realism today? Why not simply read the Gospel of Luke?

Because now, more than ever, we are cold. And it is dark. When you sit in darkness, it is hard to pray to an abstract God who reigns somewhere in unreachable empyrean heights, in warmth and light.

Antonych gives us a God who freezes alongside us.

His Christ is God-the-local, God-the-countryman. He puts on an embroidered shirt or a sheepskin coat not for ceremony, but because it is warmer that way. He knows what frozen roads feel like. He knows the wind’s howl in the chimney. He rides a sleigh over our ruts, unafraid of blizzard or night.

This is a great consolation: to know the Lord is not a foreign tourist in our reality. He is “tuteishyi” – a native. He was born here, in the epicenter of our winter.

And when we look up today into the dark sky, searching for the first star (or fearing drones), let us remember Antonych. Listen – through the sirens and the wind. Creak. Creak. Creak. Those are the runners of a sleigh.

He is already here. In our Duklia. In our heart. And in His Mother’s hands shines a golden nut of hope – a light no one will take from us.