The Quinisext Ecumenical Council: a grim picture of church life

Ten years after the Sixth Ecumenical Council, an event took place which later became known as the Quinisext (meaning “fifth-sixth”), or Trullan, Council of 691–692.

As is well known, the Sixth Ecumenical Council was convened to resolve the issue of Monothelitism. This doctrine was initiated by Emperor Heraclius, who sought religious consolidation for the empire and hoped that Monothelitism would reconcile the Orthodox and Monophysites.

It should be noted that Monophysitism recognises only one Divine nature in Christ, while Monothelitism asserts that Christ has two natures but only one Divine will. Compromises on doctrinal issues have never led to agreement, and Heraclius' initiative was no exception.

Political background

Before his death, Heraclius bequeathed the throne to his sons: Constantine III, his elder son from his first marriage, and Heraclius II from his second. However, Heraclius II’s mother, Martina, attempted to become either the sole ruler or at least the co-ruler of her son and stepson. Her attempt was unsuccessful, but the two stepbrothers did not rule for long.

Three and a half months later, on 25 May 641, Constantine III died suddenly. Historians agree that Martina was innocent of his death, though suspicion fell upon her. Moreover, Martina was suspected of planning to kill both sons of Constantine III. The matter of succession was settled by the Senate: Constantine III’s eldest son, Constantine II, was proclaimed emperor, and Heraclius II and his mother Martina were exiled. Before their exile, Martina had her tongue cut out, and Heraclius II had his nose cut off, setting a trend for the mutilation of noses in deposed emperors.

Constantine II ruled for 27 years, from 641 to 668, and was killed in Syracuse during a failed Italian campaign. Due to a series of military defeats, fratricide, heavy taxes and his adherence to Monothelitism, Constantine II was an extremely unpopular ruler. Eventually, his entourage conspired against him, leading to his assassination by a sacellarius named Andrew.

The Byzantine historian Theophanes the Confessor gives details: when Constantine II soaped his head during a bath, Andrew struck him on the head with a bucket, causing the emperor to fall into the water and drown.

Before Constantine II's departure to Italy, his three sons – Constantine, Tiberius, and Heraclius – were crowned with the titles of Augusti and considered co-rulers with their father. However, when Constantine II died, only Constantine IV Pogonatus was in Constantinople, and he was proclaimed emperor. The brothers, of course, rebelled and, backed by armed legions, demanded to be made co-rulers. Constantine IV executed the main instigators from the legions, but spared the brothers, maintaining their titles as Augusti while removing them from real power. In 680, he convened the Sixth Ecumenical Council, which took place in a friendly and respectful atmosphere and became an example of the pursuit of truth without the influence of political or other factors.

Immediately after the Council, Constantine IV turned his attention to the issue of succession. He deprived his brothers Tiberius and Heraclius of the title of Augustus and had their noses cut off. He declared his eldest son, Justinian II, as his successor and co-ruler. According to some accounts, this decision was made because the brothers had resumed their claims to power. In 685, at the age of 33, Constantine IV died of dysentery.

Justinian II (nicknamed "the Slit-Nosed") ascended the throne at the age of 16 and shocked not only his contemporaries but also future generations with his cruelty. The church historian A. Kartashev described him as follows: "He was, in general, a 'crazy' man. Insane in his governmental measures and insanely energetic. He relocated people from one region to another, started unnecessary wars, built unnecessary structures, destroying the old ones, not even sparing churches. For example, he ordered to destroy the Church of the Theotokos opposite the palace to build a fountain there. He also demanded that the Patriarch should make a prayer for the destruction of the temple. Patriarch Callinicus, despite his resistance, had to say a prayer, which he, however, concluded with a doxology: 'Glory to God, who endures always, now and ever...'."

In 689 and 690, Justinian fought against the Bulgarians and Slavs on the Danube. The war was generally successful for him, with many Slavs being captured. He relocated them to Asia Minor and formed an army of 30,000 men from them. In 692, during a war with the Arabs, initiated and later lost by Justinian, some of the Slav units defected. The enraged emperor ordered the complete destruction of all Slavs, including those who had remained loyal to him.

Justinian had two favourites – Theodotus and Stephen – who, in their abuse of power, almost surpassed the emperor himself. This disgrace led the people to revolt, led by the military leader Leontius. In 695, Justinian was arrested and his nose was cut off, and he was exiled to Chersonesos Taurica. However, we have somewhat jumped ahead, as even before his deposition, Justinian organised the Quinisext Ecumenical Council.

The Trullan Council and its Canons

The reasons for convening the Council of Trullo are rather twofold. On one hand, there was so much turmoil in church life that something needed to be done about them, and on a very serious level. On the other hand, the very idea of codifying ecclesiastical disciplinary rules, which were formulated differently in various parts of the empire, and bringing all these rules into uniformity – specifically according to the Constantinopolitan model – was very appealing to the despotic nature of Justinian.

This was intended not only to address the shortcomings of church life or at least try to do so, but also to affirm the authority of the emperor himself.

The Council was convened on 1 September 691 and held its sessions in the same hall as the Sixth Ecumenical Council. This was a hall with “trullae,” or domes, which is how it came to be known as the Trullan Council. The council was not positioned as an independent event but as a continuation of the Sixth Ecumenical Council, despite the different participants and tasks set before it. The task was formulated by the emperor himself and involved supplementing the decrees of the Fifth and Sixth Ecumenical Councils with rules of ecclesiastical discipline. For this reason, the Trullan Council is also referred to as the Fifth-Sixth (Quinsextus) Council.

The council was attended primarily by the hierarchs of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, representatives of the Eastern Patriarchates, and some Papal apocrisiarii, who did not have the status of legates and were not authorised to vote on behalf of the Roman Church. In total, it was attended by 227 bishops.

The Council sat for exactly one year, until 31 August 692, and passed 102 canons.

Canon 1 is a lengthy and Byzantine-style ornate confirmation of the dogmatic definitions of all six previous Ecumenical Councils.

Canon 2 is very important for the canonical law of the Church, as it not only confirms the canons of the first four Ecumenical Councils but also grants Ecumenical authority to the canons of certain Local Councils and certain Church Fathers. Here is a list of these canons:

- 85 canons of the Holy Apostles;

- canons of the Local Council of Ancyra (314);

- of Neocaesarea (between 314 and 325);

- of Gangra (around 340);

- of Antioch (341);

- of Laodicea (343);

- of Serdica (343);

- of Carthage (419);

- of Constantinople (394);

- canons of Saint Dionysius of Alexandria;

- of Peter of Alexandria;

- of Gregory of Neocaesarea;

- of Athanasius of Alexandria;

- of Basil the Great;

- of Gregory of Nyssa;

- of Gregory Nazianzus;

- of Amphilochius of Iconium;

- of Timothy of Alexandria;

- of Theophilus of Alexandria;

- of Cyril of Alexandria;

- of Gennadius of Constantinople.

In total, these are 625 canons, which the Trullan Council declared to be universally binding and unchangeable. Many of the canons of the Trullan Council repeat those of the aforementioned Councils and Fathers and refer to them. This means that the disorder and instability in church life, which these canons were meant to correct, had not been corrected and continued to exist. In fact, they were widespread enough for the Ecumenical Council to take notice and forbid them through its decrees.

For instance, bishops continued to live with their wives, clergy members married after ordination, entered second marriages, and married widows, prostitutes and actresses. People who had not reached the canonical age were ordained into the clergy. Metropolitans and bishops engaged in usury.

Canon 24 forbids clergy and monks "to take part in horse-races or to assist at theatrical representation".

Canon 33 denounces the practice of appointing persons of priestly descent to the clerical orders, aiming to prevent the formation of a spiritual class similar to the Jewish Levites.

There were also significant disorders within monasticism: vagrancy and frenzy; monks and nuns got married after their tonsure; and a specific canon addresses the cohabitation of nuns with clergy and laypeople.

Canon 45 forbids a custom that was practised in some women's monasteries, where women would come to their tonsure in elaborate wedding attire, "adorned in silks and garments of all kinds, and also with gold and jewels". The outfit would then be removed, and the woman would be dressed in monastic clothing. The Fathers of the Council deemed this performance inappropriate.

Canon 47, under the threat of excommunication, forbids men from spending the night in women's monasteries and women from staying in men's monasteries.

The life of the laity also had many vices and disorder, which were reflected in the canons of the Trullan Council. For example, it was common for people to attend theatres and spectacles, as well as to engage in gambling. Laypeople performed marriages within very close degrees of kinship, practised divination and spiritualism. Christmas celebrations were accompanied by superstitious rituals. Pagan vows were common, and abortions occurred.

Canon 100 forbids the depiction of what we would now consider pornography "in paintings or in what way so ever", describing such images as "those which attract the eye and corrupt the mind, and incite it to the enkindling of base pleasures", and threatens excommunication for this.

Not everything was decent in the Divine service. The priests did not teach the people or preached non-Orthodox doctrines and sold the Eucharist for money. The rich were given Communion in individual vessels, from which they then partook themselves. There were instances of the dead being communed. Grapes were placed in the Chalice of the Holy Mysteries and distributed to the people.

Canon 75 forbids undisciplined vociferations and unnatural shouting during the chanting in churches. The commentator on the canons, the confessor Nikodim (Milash), writes that this canon applies to the affected musical compositions of various secular composers, which are more suited to theatrical performances than to the Divine services.

The concluding Canon 102 outlines the principle of “economia’ when imposing ecclesiastical penance and states that it should be applied with discretion, taking into account the repentance of the sinner and their spiritual strength in order "to lead back the wandering sheep and to cure that which is wounded by the serpent”.

The Trullan Council and the Roman Church

A number of the canons of the Council were directed, in one way or another, against the traditions of the Roman Church. For example, the already mentioned Canon 2 affirms the canonical authority of the 85 Apostolic Canons, whereas the Roman Church recognised only 50 of them, and even then, not as binding but as merely recommendatory. After the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon, the Roman Church did not accept its Canon 28, which granted the Bishop of Constantinople the same privileges as the Bishop of Rome and made him second in honour. However, the Trullan Council, with its Canon 36, reaffirmed the 28th Canon of the Chalcedonian Council.

Furthermore, Canon 82 of the Trullan Council forbade the depiction of Jesus Christ in the form of a lamb, Canon 13 condemned clerical celibacy, and Canon 55 – the Sabbath fast, a practice adopted from the Jews. All of this was also accepted in Rome. Therefore, it is not surprising that Pope Sergius did not accept the Trullan Council and refused to sign its decrees.

Justinian tried to use force but failed. The Pope declared that he would rather die than sign the decisions of the Council, which he called errors. Despite the fact that Pope Adrian, 90 years later, wrote to Patriarch Tarasius of Constantinople, recognising the canons of all six Ecumenical Councils, including the Trullan Council, in general, Catholics have not recognised them to this day.

The fate of Justinian II and the revival of Monothelitism

As already mentioned, in 695, Justinian was overthrown, had his nose cut off, and was exiled. While in Chersonesus, he annoyed the local nobility with his despotic character, and the people of Chersonesus showed him open antipathy. Justinian took offence and promised to take revenge.

He escaped from Chersonesus to Khazaria, where he persuaded the local khagan to support his return to the throne. The khagan believed him and married his daughter (according to other sources, his sister) to Justinian. However, at the instigation of Constantinople, the khagan tried to kill him. Justinian then recruited a small detachment and went to Bulgaria, seeking the help of the local prince, Terbel, to help him regain power in Constantinople.

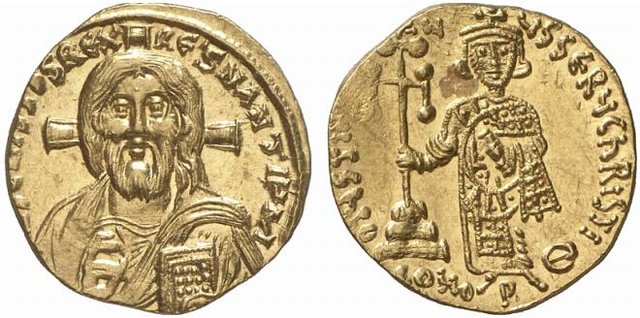

A gold coin of the time of Emperor Justinian II. Photo: coins.su

Historians report a telling detail: during the journey to the mouth of the Danube, a terrible storm arose, leaving no hope of survival. The mercenaries were so terrified that they turned to Justinian with the words: "Master, we are doomed. Make a vow to God that, if you regain the kingdom, you will not take revenge on your enemies." To which Justinian replied: "Let God drown me here, if I spare even one of them." He kept his word.

During Justinian's exile and other adventures, two rulers succeeded each other in Constantinople. In 695, Emperor Leontius took power, organising a rebellion against Justinian. But in 698, the troops rebelled against him and proclaimed a certain Tiberius as emperor. Tiberius III seized Constantinople, arrested Leontius, had his nose cut off, and imprisoned him in a monastery. However, in 705, Justinian II, with the Bulgarians, returned to Constantinople, took the city, and initiated a massacre not only of his enemies but also of anyone who happened to be in his way.

Former emperors Leontius and Tiberius were beheaded. Tiberius’ brother, the general Heraclius, and all his commanders were captured and hanged on the city wall. Justinian held banquets where he judged the invited guests to death at his own discretion. Often, those convicted were executed in cruel ways.

Patriarch Callinicus was blinded, accused of heresy, and exiled. In 710, Justinian gathered a 100,000-strong army and sent it to Chersonesus with orders to destroy the city and exterminate all its inhabitants.

The army hesitated to kill everyone, destroying only the city's nobility, and took many prisoners. Justinian demanded that they be brought to Constantinople, but along the way, a storm broke out, sinking all the ships. About 73,000 people perished. Justinian was pleased but regretted that he could not subject them to an even more brutal death. A year later, the emperor sent another army to Chersonesus with the same orders, but this time the army rebelled and proclaimed the exiled official Vardanus emperor. Vardanus, who also took the name Philippicus, seized Constantinople and killed Justinian along with his six-year-old son.

A paradox is that Emperor Justinian, notorious for his brutal cruelty, was a firm supporter of Orthodoxy and a consistent opponent of Monothelitism. Much of the reason for this was that the next emperor, Philippicus-Vardanus, swung in the opposite direction and began to promote Monothelitism. In 712, he convened a council in Constantinople that anathematised the Sixth Ecumenical Council and established Monothelitism.

However, in 713, Philippicus-Vardanus was overthrown because, in practice, he did not rule the empire, preferring feasts and debauchery with nuns. During one such feast, he was arrested while half-drunk and blinded. The new emperor was Philippicus' secretary, a man named Artemius, who took the name Anastasius II. He restored Orthodoxy, but less than two years later, he too was overthrown. The emperor became Theodosius III, again for less than two years.

In 717, he was overthrown by Leo III the Isaurian, the founder of the Isaurian dynasty, who decided to follow in the footsteps of his numerous predecessors and attempt to solve his political problems through Orthodoxy. This led to the rise of iconoclasm, condemned by the VII Ecumenical Council, which we will discuss in the next publication.