Brotherhoods: A network against an empire

In 1596, Orthodoxy in Ukraine was declared “dead.” But while elites were drifting into Catholic cathedrals, ordinary townsmen built a structure that outplayed both empire and Jesuits.

Reading documents from the late sixteenth century, one feels a distinct chill. After the Union of Brest in 1596, the Orthodox Church in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth officially ceased to exist as a legal institution. King Sigismund III Vasa simply struck it from the register of the living.

The situation seemed hopeless. Almost all bishops had entered the Union. Only two – Gedeon (Balaban) of Lviv and Michael (Kopystensky) of Peremyshl – remained faithful. They were aging. Behind them lay a vacuum. No one was left to consecrate new hierarchs, and doing so was forbidden under threat of death. The Orthodox nobility – for centuries the financial and political shield of the Church – were converting en masse to Catholicism. “Golden liberties” and seats in the Senate glittered more enticingly than the “peasants’ faith.”

Reading Meletius Smotrytsky’s Threnos (1610), one feels how the Church’s lament over its lost elites pierces through the centuries: “Where now is the house of the princes Ostrozhsky… where the families of the princes Vishnevetsky, Zbarazhsky, Sangushko, Czartoryski? Strangers surround me, my own have abandoned me!”

And then something happened that can only be called a historical miracle. When the “generals” deserted, the “rank and file” went into battle.

Bakers against Jesuits

The brotherhoods grew out of ordinary craft guilds. Bakers, mead-makers, tanners gathered in their associations, pooled funds, brewed beer for shared feasts. But under persecution these “trade unions” became a powerful network.

In January 1586, the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood received an extraordinary status – stauropegia. Patriarch Joachim V of Antioch, passing through Lviv, and later Patriarch Jeremiah II of Constantinople, granted laymen the right to answer directly to the Ecumenical Throne, bypassing local bishops who had defected. The patriarchal charter declared: “Let every brotherhood founded anywhere conform to the statutes of the Lviv Brotherhood.” One guild became a model for a pan-Orthodox network from Kyiv to Vilnius.

The audacity of these townsmen is astonishing. The Brotherhood could discipline its members for drunkenness or immorality – but more than that, it could stand up to a bishop.

“If a bishop acts against the law… let the Brotherhood oppose him as an enemy of truth.”

This was a direct challenge to the feudal order. Laypeople gained legal immunity from arbitrary hierarchy. That immunity saved the Church when the hierarchy betrayed it.

An intellectual special forces

These “simple townsmen” proved wiser than many princes. They understood: to defeat the Jesuits – Europe’s intellectual elite – one must fight with their weapons. In 1615 the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood was founded. And here is a detail that still startles.

On October 14, 1615, a widow, Halshka Hulevychivna, entered the Kyiv land court and donated her estate in Podil – prime real estate bordering the mayor’s and treasurer’s homes – to establish a monastery, a school “for children of the nobility and of townsmen alike,” and a hospice. No bargaining. No conditions. Only one clause: if the property ever passed into non-Orthodox hands, her descendants could reclaim it.

At the Brotherhood school, students drilled Latin. Why?

To speak in courts, in parliaments, in public debates in the enemy’s tongue – and win.

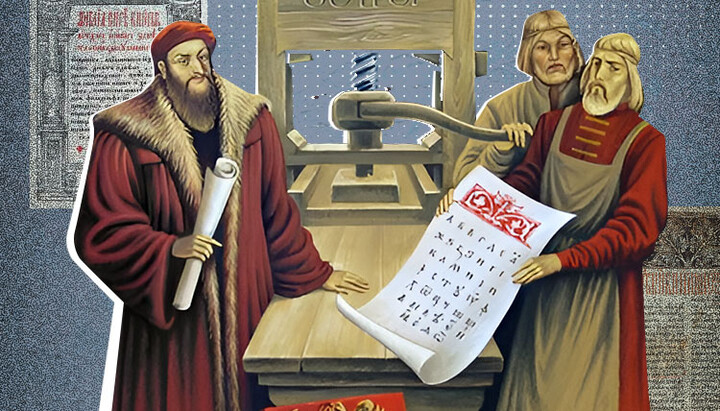

Christophor Philalet published Apokrisis. The Zizani brothers wrote grammars. Brotherhood members bought Ivan Fedorov’s printing press in Lviv. Education and printing became their shield. Orthodoxy ceased to be the “faith of simpletons” and became the faith of intellectuals who could defeat any Jesuit in open debate.

Where did fishmongers and cloth merchants find such hunger for enlightenment? They poured vast sums into mills, shops, entire villages – simply to fund schools and print books.

A cossack umbrella

By 1620, the situation reached breaking point. For twenty-five years Orthodox Christians in Ukraine had lived without a legitimate metropolitan. The hierarchy was burned to ash. Then one move changed everything.

In August 1620, at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, a secret council met. Patriarch Theophanes III of Jerusalem was passing through Kyiv. He feared Polish retaliation – rightly so. Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny made a move worthy of a grandmaster. He enrolled himself in the Kyiv Brotherhood – and enrolled the entire Zaporizhian Host with him.

It was an ultimatum to the king: the Church was no longer a mass of powerless peasants. It was forty thousand sabers.

Under Cossack protection, on October 9, 1620, in the Epiphany Church of the Brotherhood Monastery, Patriarch Theophanes consecrated a new hierarchy “from the ashes.” Saint Job (Boretsky), former rector of the Lviv and Kyiv Brotherhood schools, became Metropolitan of Kyiv. Several bishops were appointed.

King Sigismund responded predictably. His edict branded Theophanes a “spy of the Turkish sultan” and the new bishops traitors who “without our will and permission dared to accept consecration.” But he did not arrest them. Poland was preparing for war with the Ottomans at Khotyn. He needed the army. Sahaidachny had placed a military umbrella over the Church.

The new hierarchy survived de facto for thirteen years – until 1633, when King Władysław IV finally recognized it legally.

A victory that almost destroyed its authors

Once the hierarchy was restored, something paradoxical happened. The new bishops began pushing back against the brotherhoods. They wanted to restore vertical authority. Laypeople, accustomed to decades of autonomy, resisted.

In 1626 Archbishop Meletius (Smotrytsky) – the same who had written Threnos – secured from Constantinople the abolition of most stauropegia. Only Lviv and Vilnius remained. The circle closed: laypeople had saved the hierarchy; the hierarchy sought to rein them in.

This conflict was a sign of vitality. The Church was alive – arguing, struggling, thinking. It was civil society in the highest sense: real power, real money, real responsibility for faith.

Brotherhood records preserve the spirit, if not always the exact phrasing: “We are simple townsmen, but we will not sell our faith.”

Today, when people speak of threats to the Church, legal pressures, attempts to push it out of public life – remember those bakers and tanners who bought printing presses and funded schools from their own pockets. They did not wait for rescue. They became a state within a state.