“The Fly Syndrome”: Elder Paisios on how to see flowers in a minefield

An Athonite test of spiritual sanity: why some find filth in a paradise garden, while others discover honey in a field of ashes.

There are moments when it seems we have forgotten how to breathe. The air itself feels dense and acrid – as if saturated with the anxious anticipation of misfortune. We move along streets that once felt like home with the caution of sappers, afraid to hope, afraid to smile, afraid to allow even a small flicker of trust lest sorrow rush in and smother it.

Our souls have grown a crust of defensive cynicism. We convince ourselves that if we expect the worst, we will be spared its sting. We call this posture “sobriety” or “bitter truth,” yet all the while we are suffocating inwardly, losing the capacity to see beauty, to perceive grace, to taste joy.

And this state of chronic suspicion, of darkened vision, exhausts us more thoroughly than any physical toil ever could.

We peer at the world through soot-stained glass, and even the sun, benevolent by nature, appears cold and threatening. But was this the purpose of our creation – to shrink into fearful creatures hiding in dark corners, waiting for calamity? If we hope to rise from this pit of dread, we must learn again to see, to choose where to direct the gaze of the heart.

Aivazovsky lessons

Stand before Ivan Aivazovsky’s The Ninth Wave. Humanity appears small, fragile – a few figures clinging to the remnants of a ship as the sea towers above them, poised to crush. It should evoke despair. And yet, the more we look, the more a strange, luminous strength begins to stir within us.

The secret is in the focus.

Aivazovsky does not compel us to drown in the darkness. He leads our eyes to the golden shaft of light cleaving the storm.

The sun is rising. Even amid destruction, the painter insists on hope. He reminds us that the human being possesses one final, inviolable freedom – the freedom to choose where to look. We can stare into the abyss and freeze, or we can lift our eyes to the light that reigns above the storm.

Today, perhaps more than ever, we need this “Aivazovsky sight.” But where can we learn it? Let us travel, in the quietness of imagination, to Athos – to the little cell of Panagouda, where Elder Paisios once lived. Let us sit beneath the whispering pines and ask him what he sees in a world so torn.

The Elder who had seen war, who had smelled fire and death, yet whose eyes always shone with a joy born of Resurrection.

What are we: forest healers or gatherers of decay?

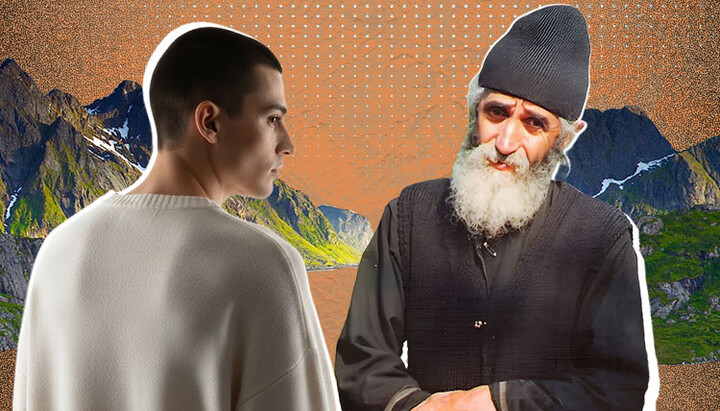

We approach him weary, bruised, laden with grievances. We want to complain about injustice, cruelty, and the madness of a world that seems to be crumbling.

“Geronda, how can we live when so much evil surrounds us? We see only hypocrisy, ruin, lies. How can one turn away? Isn’t it dishonest to pretend otherwise?”

The elder looks at us with compassion, yet he does not validate our indignation. Instead, he offers a parable of startling simplicity – a test of spiritual vision:

“Some people are like the fly. A fly always seeks what is foul. Even if a garden is filled with fragrant blossoms, and in one corner there lies a heap of refuse, the fly will pass over the entire garden without touching a single flower. It will find the filth, land on it, and begin to dig.”

These words fall on us like cold rain. In an instant we recognize ourselves: scrolling endlessly through sorrow and outrage, seeking the one story that will confirm our bitterness. We pick at wounds, real or imagined. But the elder does not leave us in this pit; he sets before us a different creature:

“Others are like the bee. The bee searches for what is sweet and beautiful. Even if a room is filled with filth, and in a corner someone has placed a single flower, the bee will fly past everything else and settle only upon that flower.”

“But geronda,” we whisper, “we do not choose this. The world itself is so dark, so cruel. We merely react.”

He gently disagrees. The world certainly contains shadows, but shadow alone cannot explain our fixation. The elder sees deeper:

“Those who resemble the fly seek out something bad in every situation. They fail to notice even a trace of good. Those who resemble the bee find what is good everywhere.”

The factory of the mind

“All right,” we sigh, “we long to be bees. But how can we change the mind, which for years has learned to feed on negativity? The anger feels automatic.”

Elder Paisios shakes his head. Nothing about it is automatic. The mind is a workshop, a factory, and we are its craftsmen:

“People with good thoughts have their minds tuned toward good. They operate a factory of good thoughts. Those with darkened hearts run a factory of evil thoughts. The most profitable enterprise a person can begin is the factory of good thoughts.”

Life delivers the raw material – often harsh, often stained. Yet the transformation depends entirely on the worker. Someone shouts at us or treats us unjustly. The factory of evil immediately manufactures resentment. The factory of good produces a different response:

“Poor soul… perhaps he is struggling, perhaps he has sorrow. Lord, have mercy upon him.”

Without this craftsmanship, the elder warns, darkness invades the unguarded mind:

“With evil thoughts, a person unjustly wounds others and blocks divine grace. Then the devil comes and tears him apart.”

When the earth trembles

We ask the question that sits deepest, the one that burns:

“Father… good thoughts help in daily irritations. But what about vast evil – innocent lives lost, cruelty triumphant, truth trampled? How can one not despair? How can one bear the silence of Heaven?”

The elder grows solemn. He knows these storms. And he speaks not from naivety but from the depth of someone who has stared into the abyss and refused to collapse:

“I would have gone mad from the injustice of this world if I did not know that the final word belongs to the Lord God.”

This is the axis on which the universe turns. We tremble because we see only the middle of the story. God sees the end. We witness fragments; He beholds the whole.

“God endures because He has patience. But everything has a limit. God will take up the broom. Trust in God is a great thing. These years are very hard and very dangerous, but in the end Christ will prevail.”

“And the fear?” we whisper. “The fear for our homes, our children, our tomorrow?”

The elder does not soften the truth:

“We did not come into this world to make ourselves comfortable. The fear of God turns even the greatest coward into a brave man. The more a person is united with God, the less anything can terrify him.”

A one-day pilgrimage of the heart

The conversation in Panagouda draws to a quiet close. The sun slips behind Athos. It is time to return to the world. Yet we leave not empty-handed. The elder has given us a task: to train the gaze of the soul.

Let us try a simple experiment. For one day, let us live like the bee. We hear a frightening rumor – let us not repeat it. We see destruction – let us search for the surviving tree, the sliver of sky, the breath still in our lungs. Someone wounds us – let us pity them as one wounded by sin, and not wound them in return.

It is terribly hard. It is perhaps the hardest discipline of all. Yet it is the only way to keep darkness from nesting within the heart.

As we depart, the elder leaves us with a final word – a formula of spiritual clarity:

“A person who is corrupted thinks in a corrupted way; he approaches everything with prejudice and sees it inside out. But the one who has good thoughts – whatever he sees or hears – immediately sets his good thought to work.”