The Pope in exile: Where the story of persecution of our Church began

A Roman aristocrat who became a convict in Crimea. The story of St. Clement opens our new series on the history of persecution of the Church on Ukrainian lands.

We tend to imagine that Christianity arrived to us wrapped in gold and purple, with the solemn baptism of the Kyivans in the waters of the Dnipro. But the historical truth is harsher. The foundations of our Church are not laid upon Byzantine splendor but upon limestone dust, sweat, and the blood of martyrs.

With this article we begin a major historical cycle, Chronicle of Persecutions. We will trace the Church’s path through the centuries on Ukrainian soil – from Roman shackles to Soviet camps and our present trials.

And we begin at the zero kilometer of this road. At the place where, at the end of the first century AD, the very “anchor” was dropped that still holds us fast in the storm.

The setting: the quarries of Inkerman.

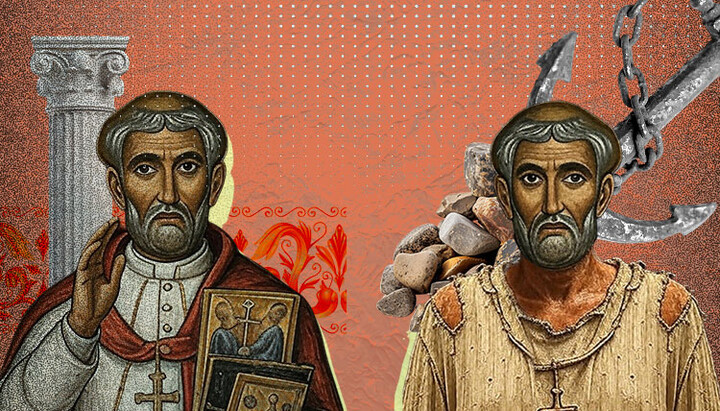

The protagonist: the third Bishop of Rome, a man who personally knew the apostles Peter and Paul – whose memory the Church celebrated this week (December 8).

Exile as a technology of erasure

The year is 98 AD. Marcus Ulpius Trajan ascends the Roman throne. History will remember him as “the best of emperors,” a builder and commander under whom the Empire reached its greatest territorial extent. But for Christians he was a cold pragmatist who set the bureaucratic machine of repression into motion.

It was Trajan who formulated the legal principle of persecuting Christians (known from his correspondence with Pliny the Younger): they were not to be sought out deliberately, but if denounced and refusing to recant – executed. Christianity was declared a religio illicita – an illegal religion.

Clement, Bishop of Rome, was far too prominent a figure to simply execute in the Colosseum.

A public death could have turned him into a hero of imperial stature. Trajan chose a more refined means of elimination – damnatio memoriae, the erasure of memory, through exile to the farthest fringes of the oikoumene.

He was sent to Chersonesus Taurica (modern Sevastopol). For a Roman of the time, this was the “end of the world,” a wild frontier from which no one returned. But even Chersonesus was too civilized. Clement was sent further still – to the quarries of Kalamita, Inkerman.

The hell of white stone

What kind of punishment was this? To a modern tourist, Inkerman looks picturesque. But in the first century it was an industrial hell.

The limestone here is bryozoan – soft when cut, but hardening upon contact with air. It was an ideal building material for the Roman fortifications in Crimea. Quarrying was done both in open pits and underground shafts.

The working conditions were designed to kill slowly. First, the heat. White stone reflects sunlight. In summer, the quarry bowl reached 45–50°C (113–122°F). Second, the dust. A dense cloud of lime hung in the air. With every breath it settled in the lungs, mixing with moisture and turning into cement. Silicosis killed workers in two to three years. Third, the work quotas. Roman logistics were ruthless: stone was constantly needed for forts and roads.

By the time Clement arrived, about two thousand Christians were already laboring in the tunnels. They were people with brand marks on their faces, often with nostrils torn out (a sign of runaway slaves or criminals), shackled in chains.

The Pope of Rome, an intellectual and likely an aristocrat of the Flavian line, took a pickaxe in his hands. He was over sixty – an old man by ancient standards.

The logistics of survival

His Life recounts a miracle: that God, the Lamb, revealed to him the place in the rock where a spring burst forth. This is often read as poetic allegory, but let us view it through the lens of physiology and topography.

The Inkerman heights form a dry plateau. The nearest water source, the Black River, lay below in a marshy lowland and was unfit for drinking – stagnant and brackish due to its proximity to the sea. Drinking water had to be carted in under armed guard.

Dehydration during heavy labor in the heat sets in within three to four hours. Symptoms: thickening of the blood, hallucinations, kidney failure, heatstroke. The exiles died not from hunger but from thirst.

Clement’s discovery of fresh water inside the limestone itself (karst cavities are not uncommon in Crimea, yet extremely difficult to locate) became a turning point. This was a matter of physical survival. With access to water, the community ceased to depend on their overseers.

This allowed Clement to establish what today we might call a “network structure.” The quarries became a vast subterranean church. Archaeological excavations in Inkerman confirm that many of the cave chambers later used as monastic cells were originally cut as utility and worship spaces during the Roman period.

Rumors of the “Roman priest” who brought water and hope spread through the surrounding settlements – Scythians, Sarmatians, Greek colonists. His Life speaks of “500 baptisms a day.” Even if this number is exaggerated, the scale of the mission was extraordinary. Over his three years of exile (99–101 AD), Clement turned Crimea into a Christian stronghold.

Technology of execution

In 101, the imperial envoy Aufidian arrived in Chersonesus. The reason: reports that the exiled Christians were not dying out but instead converting the local population. Trajan demanded a “final solution.”

Aufidian acted harshly. Many Christians were executed on the spot. But for Clement a special death was prepared.

He was taken out by boat into the open sea (either Kazachya Bay or the outer waters of Chersonesus). An old iron anchor was tied to his neck. And he was cast into the depths.

Why so elaborate? Why not a sword or crucifixion? The Romans understood the cult of martyrs. They knew: if a body was buried on land, the tomb would become a pilgrimage site and a center of resistance.

Drowning with a heavy stone ensured the body would never be found. The water was meant to erase the memory of the third Pope.

But the executioners made a symbolic miscalculation. In Roman culture, an anchor – ancora – was merely a nautical tool. But for Christians of that era it was already a secret symbol. In the first- and second-century Roman catacombs, anchors appear as disguised crosses. The Apostle Paul calls hope “a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul” (Heb. 6:18–19).

By drowning Clement with an anchor, the pagans inadvertently illustrated Christianity’s central metaphor. They sought to destroy the Bishop – instead they gifted the Church an eternal symbol: faith is what holds you fast even at the ocean floor.

The first brick in the foundation of Kyiv

What does first-century Inkerman have to do with Kyiv? The connection between this Roman convict and the Baptism of Rus’ is a historical fact, confirmed by chronicles.

Clement’s body, contrary to Roman intent, was recovered. Until the ninth century his relics were kept either in an underwater grotto (exposed at low tide) or on a small offshore islet. In 861, the renowned “Khazar Mission” arrived in Chersonesus – Saints Cyril and Methodius. They organized a search, found the relics, and took part of them to Rome. It was precisely the presence of St. Clement’s relics – venerated by both East and West – that persuaded Pope Adrian II to permit the brothers to use Slavonic in worship. Without Clement, we might not have had Cyrillic.

A century later, in 988, Prince Volodymyr captured Korsun (Chersonesus) and brought the head of St. Clement to Kyiv.

Reflect on this: the relics of St. Clement were the first Christian holy treasure of Rus’.

The Church of the Tithes – Kyiv’s first stone temple – was constructed specifically as a reliquary for the head of Clement of Rome.

Before the canonization of Boris and Gleb, before Saints Anthony and Theodosius of the Caves, it was St. Clement who was regarded as the heavenly patron of Kyivan Rus’. Our ecclesial identity, our history, was built upon the bones of a martyr who had endured Roman exile.

Epilogue

Today we once again face dark times. Churches are being closed, priests put on trial, believers pushed into a ghetto of silence. Many fear this is the end.

But the story of St. Clement teaches the opposite. Christianity on our lands did not begin with state patronage – it began with forced labor. The first bishop to set foot here was a convict in a quarry.

The Roman Empire with its legions, prefects, and almighty Trajan crumbled into dust. Nothing remains but ruins for tourists. But the Church that Clement built in the dust of Inkerman still stands.

The “anchor” dropped in 101 off the Crimean coast still holds us fast.

The storm may tear our sails to shreds –

but it cannot move the rock beneath us.