The Oath Book: Secrets of Peresopnytsia Gospel

It weighs nine kilograms and still remembers Mazepa’s hands. The story of the first Gospel translation that became a national symbol not because of gold, but because of meaning.

On the Day of Unity we are used to speaking about geopolitics, the “Act of Unification”, and the joining of the Dnipro’s banks. But there is another unifier – older and more silent – one that appears on live television on every channel every five years.

We watch a president’s hand settle onto the velvet of the binding. We hear the anthem. We feel the solemnity of the moment. But few people stop to ask: what, exactly, lies beneath that palm?

If we switched off the pathos and turned on the scales, we would see this: under the hand lies 9 kilograms and 300 grams of history.

It is 482 leaves of parchment. Not paper, but parchment – finely dressed skin of young lambs. If you have ever held an old parchment book, you know the sensation. It is warm. It is alive. Unlike dead cellulose, parchment has texture – pores, scars. It is flesh that has become word.

But the main weight of this Book is not in its material. It is the first time in our history that God spoke to the people not in the solemn, yet barely understood Church Slavonic, but in the living, juicy, “peasant” speech of the sixteenth century.

History’s paradox: a book created so that ordinary people could read it and understand it became an elite symbol – something only the chosen are allowed to touch.

A woman’s trace – and the “simple tongue”

Every great startup has an investor. The Peresopnytsia Gospel’s investor was a woman.

Mid-sixteenth century. Europe is boiling. Luther has already translated the Bible into German, making religion understandable to the burgher. In Catholic Poland, translations are beginning as well. And what about us?

We have Princess Anastasia Zaslavska (in monastic life, Paraskeva). A woman from the highest Volhynian aristocracy who commits an act of intellectual courage that was almost unthinkable.

She commissions a translation of the Four Gospels into the “simple tongue”.

This was not the whim of a wealthy widow. It was deliberate cultural policy. The princess understood: if faith does not become understandable, the people will go where it is understandable – to Protestants or to Catholics.

She hires a “project manager” – Archimandrite Hryhorii from the monastery in Dvorets – and a gifted calligrapher and translator, Mykhailo Vasylievych, the son of a proto-priest from Sanok.

The work begins on August 15, 1556. Imagine the labor. This is not typing on a keyboard. This is preparing ink by hand from oak galls that, with time, turn rust-brown. It is grinding cinnabar and gold leaf.

They worked for five years. They completed the work already at the Peresopnytsia Monastery on August 29, 1561. In the afterword – the colophon – the scribes left us a key to the purpose of this Book.

They write that this labor was undertaken “for the better understanding of the common Christian people”.

Think about that. Not for beauty. Not for a museum shelf. But so that the “common folk” could “understand” Christ. This was a book as enlightenment – not a book as an idol.

A survival detective story: Mazepa and the NKVD

The fate of the Peresopnytsia Gospel resembles the biography of an adventurer who miraculously survives shootouts. Books, like people, burn, vanish, and die in wars. But this folio passed through fire – literally.

In 1701 the Book falls into the hands of Hetman Ivan Mazepa. Mazepa was a great patron and, in modern terms, a master of PR. He understood the value of rarities. The hetman takes the Gospel from an out-of-the-way monastery, restores it (it was likely he who dressed the book in its present luxurious binding), and presents it to the Pereiaslav Cathedral.

On the first pages his dedicatory inscription has survived: “This Gospel… was set in order at the cost and expense of His Grace Pan Ivan Mazepa… and granted to the throne of Pereiaslav… in the year 1701.”

And then the obstacle course begins.

- Nineteenth century – the book ends up in the library of the Poltava Seminary. There it is found and brought into scholarly circulation by Osyp Bodianskyi (a friend of Shevchenko).

- Twentieth century – the most terrifying time. Revolution, civil war. The book is saved by museum workers in Poltava.

- 1941. The Nazis advance. Evacuation. Thousands of exhibits are abandoned or burned. But the Peresopnytsia Gospel is taken deep into the rear – to Ufa.

It survives Nazi occupation. It survives Soviet atheism, when keeping religious literature could earn you a prison term. Why didn’t the Communists destroy it? Because it was classified as a “monument of language”, not an “object of worship”. Again, irony: philology saved theology.

Today the Peresopnytsia Gospel is kept in the Institute of Manuscripts of the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv. In a special safe, under strict humidity and temperature control. The book rests from its turbulent journey, leaving the repository only for inaugurations.

Beauty in the margins

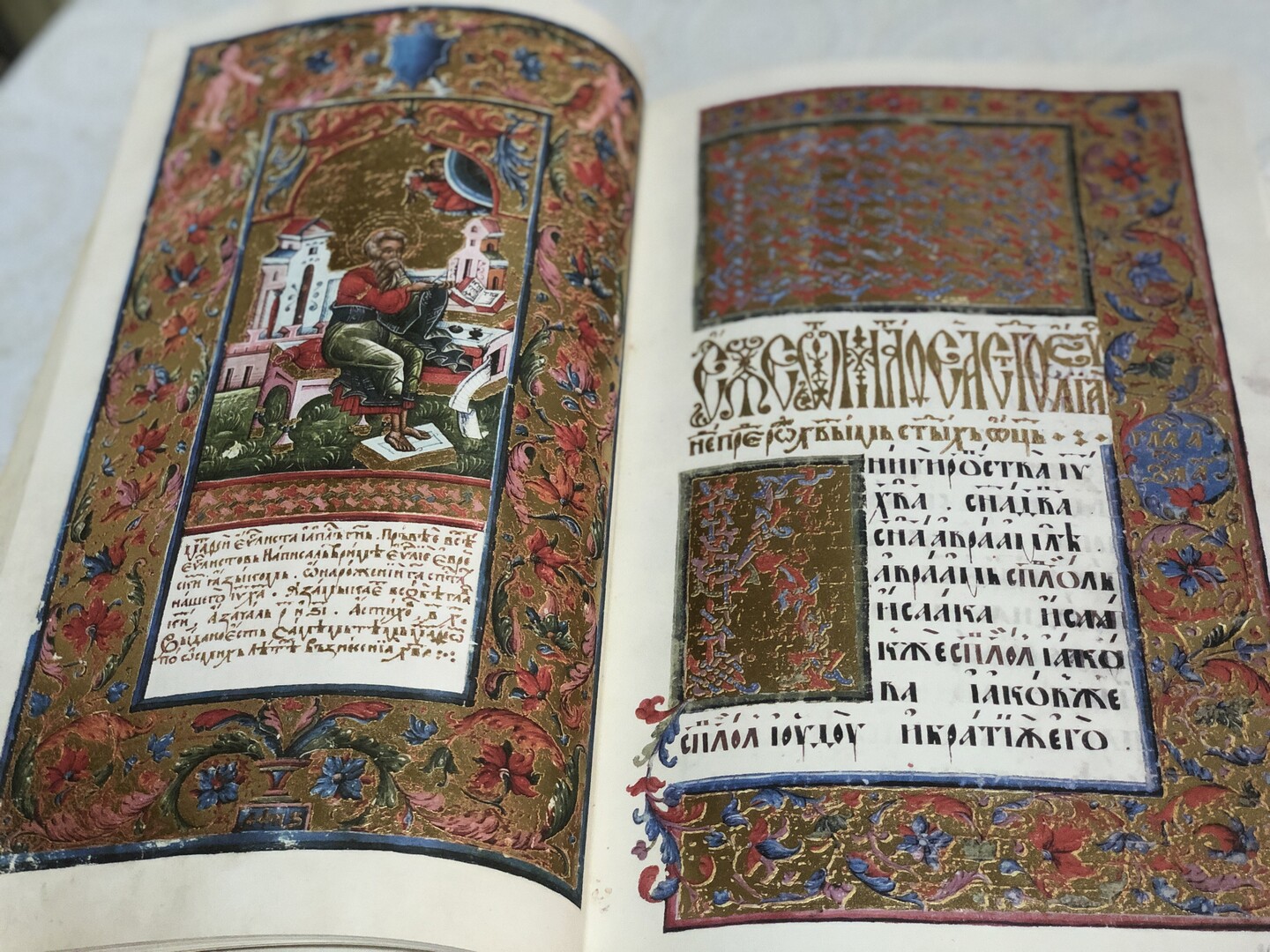

If we were allowed (with gloves, of course) to leaf through this volume, we would be surprised. It is not strict Byzantine canon.

The Renaissance blooms on the pages of the Peresopnytsia Gospel.

Ornaments, frames, initials – all of it resembles Italian models, but with a local, Ukrainian flavor. There is realism here. There is joy of life. The miniatures of the Evangelists are painted on a golden background, yet their poses are alive, not static. They write, they think, they sharpen their quills.

The book is beautiful with that noble, heavy beauty that cannot be imitated on a printer. For 450 years the ink has bitten into the parchment for good. The gold has dimmed, but it has not flaked away. This is craftsmanship built for eternity.

Hand and heart

Today, on the Day of Unity, we will again see footage of this Book. It has become a state symbol – a kind of “Ukrainian Grail”. That is honorable, but also a little sad.

Because Princess Zaslavska spent a fortune, and the monk Mykhailo ruined his eyesight by candlelight not so that a hand could be laid upon the book. They wanted the book to be opened.

They wanted the words of the Gospel to sound intelligible. They wanted the barrier between God and man – built of incomprehensible terms and an alien language – to collapse.

The Peresopnytsia Gospel is a monument to the thirst for meaning.

It weighs nine kilograms, but its true heaviness is not in the oak boards of its binding or in the silver of its cover. The weight of this Book is responsibility. The one who places a hand on it swears not before a museum and not before a constitution. He swears before the Word that was in the beginning.

Perhaps the greatest honor for this Book is not when it lies closed on a velvet stand under the aim of cameras, but when someone – even only in the mind – tries to read through the centuries the lines drawn in reddish ink, written for the “common folk”. Because the Book is alive as long as it is read.