A knife in the back from your own: Why St Nektarios didn’t leave the Church

They slandered you – the very people who stood with you at the one Chalice? You want to slam the door and walk out? A conversation with a saint who waited a hundred years for justice – and defeated the system with an ordinary mop.

I’m standing by the monastery walls, and I want to scream. I was betrayed. Again. By the very ones I was chanting an akathist with yesterday. The ones I trusted with the keys to my home and to my own soul. The ones who called me “a brother in Christ” – and today pretend they don’t know me, because it’s more convenient that way, safer for their careers. “The Orthodox will devour you and not even choke” – I’ve heard that a hundred times, but now it isn’t a figure of speech. It’s the taste of blood in my mouth.

Inside – scorched earth. If the Church is “family,” then why does this family strike so expertly, right under the ribs?

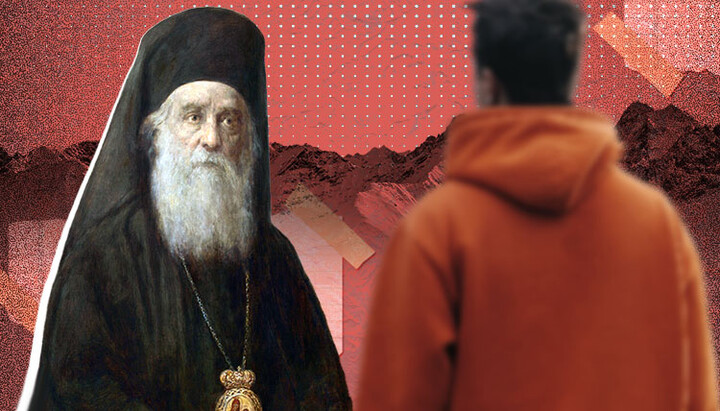

St Nektarios of Aegina isn’t sitting on a gilded throne. He’s digging earth for future olive trees. His cassock has faded into ash-grey; on his hands – calluses that a metropolitan has no business having.

“Vladyka, why did they keep silent?” I’m almost shouting at his back. “They watched me drown! They took Communion with me yesterday – and today they’re signing denunciations. Where is God in any of this?!”

The saint doesn’t turn at once. He drives the spade into the stony ground. Crunch. The sound of metal on rock, in that stillness, lands like a sentence.

“They weren’t silent,” he says at last, turning. “They were screaming. Not with words – with their indifference. And that is louder than any cry.”

The Athenian pier and the smell of tobacco

He sits on a rough boulder and looks out to sea. In 1890 he stood on a similar shore – only in Athens. Banished from Egypt. Patriarch Sophronios of Alexandria signed the decree of his dismissal without a single explanation. Simply: “dismissed.” No severance, no documents, and the brand of “unreliable.”

“I stood in the port of Piraeus,” the saint recalls. “Not a drachma in my pocket. People I considered friends passed by – priests I had helped, officials I had counseled. They hid their eyes. They smelled of expensive tobacco and the fear of catching my ‘disgrace.’”

I look at his worn, greasy cassock, at his scuffed boots, and I feel sick. Ashamed of my new jacket, my warm office, my “great” grievance. They stole his life – and he still didn’t buy a one-way ticket out of the Church.

“Why didn’t you sue them, Vladyka? Why didn’t you go to the newspapers and expose how the Patriarch was rotting in intrigue? You had proof!”

“To defeat vileness, you can’t use its tools,” he looks at me the way you look at a child. “The moment you start fighting for your ‘honor’ with foam on your lips, you lose Christ. Christ was silent before Caiaphas. I decided His silence was my only chance to remain human.”

The physics of a mop

There was a moment in his life that strikes harder than any dogma. When he became headmaster of the Rizarios School in Athens, the faculty rose against him. Too simple. Too generous to the poor. Too disruptive to their “order.”

We’ve already recalled the story of how, one day, the school’s only janitor fell ill – an old, frightened man who feared he’d be thrown out if he didn’t come to wash the floors.

And then Metropolitan Nektarios, the headmaster, began rising every morning at four. While the city still slept in bluish pre-dawn twilight, he would go into the toilets. He would take a bucket, a coarse brush, and scrub the icy stone floors. He cleaned the latrines after his students and colleagues – while those same colleagues were composing yet another complaint against him.

“That was my answer,” the saint says. “Not to them. To God. I washed those floors, and I felt – with every drop of filthy water – my resentment draining out of my soul. You can’t stay offended at someone whose toilet you are cleaning. You simply see his weakness. His poverty.”

This isn’t some “humble elder” from a pious paperback. This is a steel man who chose a mop instead of a sword, so that hatred would not eat him from the inside.

Justice, a hundred years later

“Vladyka – but it’s unjust! For a whole century your persecutors were listed as ‘respectable,’ while you were ‘suspicious.’”

“God allows us trials from our own, so that we may seek consolation only in Him,” he repeats the thought from his letter to the nuns, and I feel the chill of marble tiles in that hospital where the metropolitan died alone.

“If you love the Church for ‘nice people,’ for ‘kind fathers’ and ‘fairness,’ you will leave at the first scandal. You will find vileness everywhere.”

He pauses. The wind dies down for a moment.

“But if you came to Christ, then a knife in the back from a brother is simply part of His road to the Cross. Betrayed? Congratulations. You’ve come a little closer to Him. He stood there too – in the praetorium – utterly alone, while His ‘own’ scattered, or warmed themselves by the enemies’ fire.”

Catharsis

I’m silent. The smell of incense from his cassock mingles with the smell of dry grass.

It still hurts. The wound hasn’t closed; it’s still bleeding. But suddenly I understand one thing. If I leave now, if I abandon the temple because of those who struck me – then they win. Then they become more important to me than God. Then I was worshiping not Christ, but my own comfort inside the parish.

“Will it hurt, Vladyka?” I ask quietly.

St Nektarios returns to the spade. Again that crunch of rock.

“It will. And not once. But now you are not alone. You are in the company of the One they also drove beyond the gates.”

I watch him dig. A bishop with dirty hands. A man the Church failed to notice for a hundred years – and who became Her heart.

There is no final conclusion. Only this prickly wind, and the knowledge that the Church is not about us – the “good ones.” It is about Him – the Only One who will never betray. Even if all your “own” sign your sentence.